Named Entity Recognition is a common application for LLMs, but most implementations default to hosted APIs without evaluating whether the task requires that overhead. For structured extraction with clear schemas, smaller local models frequently match larger hosted alternatives while eliminating per-token costs and data privacy concerns.

This case study presents a methodology for contact data extraction using a quantized local model. The focus is practical: prompt structure that produces consistent output, two-pass processing that catches autoregressive errors, and validation that confirms results before production use.

Context and Problem

Named Entity Recognition (NER) involves extracting specific pieces of information from unstructured text: names, addresses, dates, dollar amounts, and similar structured fields. It is foundational to document processing, data migration, and system integration.

Traditional approaches rely on regular expressions, rule-based parsers, or dedicated NER libraries. These work well when input formats are predictable. They fail when they aren’t.

Real-world data rarely cooperates. Contact information arrives in dozens of formats: some entries have email first, others phone; some use full state names, others abbreviations; some include ZIP codes, others omit them. Building and maintaining regex patterns for every variation becomes its own project.

LLMs handle this variability through contextual inference rather than explicit pattern matching.

Hardware and Model Selection

This work was performed on a workstation with an NVIDIA A4000 (16GB VRAM). The A4000 is a professional GPU that balances cost, power consumption, and capability for local inference workloads. Consumer GPUs like the 16GB NVIDIA 5070 Ti and even older models like the 24GB 3090 or 4090 are also sufficient for these tasks.

Model: Microsoft Phi-4, quantized to 8 bits per weight (8bpw) using ExLlamaV2. This quantization level fits comfortably in 16GB VRAM while leaving room for KV cache and activations.

These smaller models also run on modern desktop PCs using just a CPU and RAM via llama.cpp (code-based) or LM Studio (GUI), albeit more slowly. For batch processing where latency isn’t critical, this remains a viable option.

The choice of Phi-4 is deliberate. For structured extraction tasks with clear instructions, smaller models often match larger ones. The cost-per-token advantage of local inference compounds quickly when processing thousands of records.

The Task

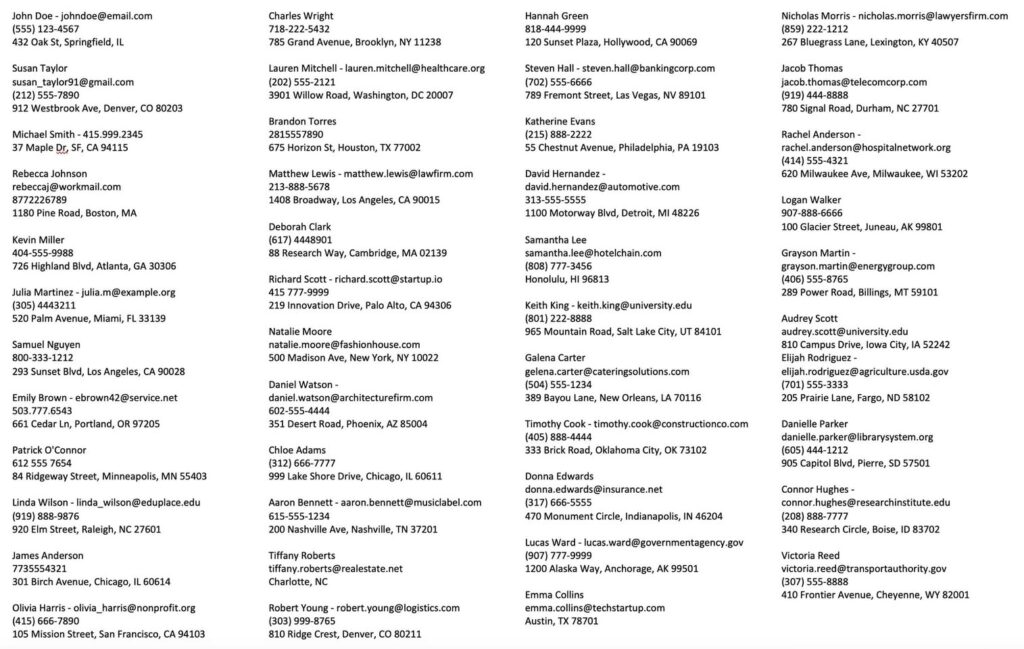

Input: 48 contact records in inconsistent formats. Some include email addresses, others don’t. Phone number formatting varies (parentheses, dashes, periods, spaces). Address components are sometimes on one line, sometimes split across multiple lines. State names appear as both abbreviations and full names.

Output: Clean CSV with consistent columns: Name, Email, Phone, Address, City, State, Zip.

Requirements:

- Standardize phone numbers to (XXX) XXX-XXXX format

- Separate street address from city, state, and ZIP

- Handle missing fields gracefully

- Flag entries that need human review

The Prompt

Prompt engineering for extraction tasks benefits from explicit structure. The following prompt defines the output schema, provides formatting rules, includes an example, and specifies error handling:

Objective:

Extract structured contact information from the provided unformatted text

and convert it into CSV format with specified columns. Capture all available

information, even if some fields are missing. Format all phone numbers as

(XXX) XXX-XXXX and ensure city and state are captured separately from the

address.

Columns to Extract:

- Name: Full name of the person (e.g., "John Doe")

- Email: Email address of the person (e.g., "johndoe@email.com")

- Phone: Phone number formatted as "(XXX) XXX-XXXX" (e.g., "(555) 123-4567")

- Address: Street address without city, state, or ZIP (e.g., "432 Oak St")

- City: Full city name (e.g., "Springfield")

- State: Two-letter state abbreviation (e.g., "IL")

- Zip: Postal ZIP code (e.g., "60901")

Instructions:

1. Read the Unformatted Text Carefully: Identify and extract each piece of

information based on common patterns and keywords.

2. Use Patterns for Extraction:

- Phone Numbers: Look for patterns like "(XXX) XXX-XXXX" or "XXX-XXX-XXXX"

and reformat to "(XXX) XXX-XXXX".

- Email Addresses: Identify email patterns using "example@domain.com".

- Addresses: Extract street addresses and separate them from city, state,

and ZIP code information.

3. Identify Keywords and Phrases:

- Use common indicators like Email:, Phone:, Address:, City:, State:,

and ZIP: to locate relevant data.

4. Format Data into CSV:

- Enclose each field in double quotes.

- Separate fields with commas.

- Ensure no extra spaces around commas.

5. Handle Missing Data:

- Leave fields blank if no information is available.

- Include city and state if known, even if other fields are blank.

Error Handling:

- Flag Entries for Review: Identify entries with incomplete data for manual

review.

- Correct Misplaced or Incorrect Data: Adjust any misplaced data or incorrect

formatting according to the specified rules.

Example:

Given the unformatted text:

John Doe - johndoe@email.com

(555) 123-4567

432 Oak St, Springfield, IL

The extracted CSV should be:

"Name","Email","Phone","Address","City","State","Zip"

"John Doe","johndoe@email.com","(555) 123-4567","432 Oak St","Springfield","IL",""

Data to process:

Why the Example Matters: In-Context Learning

LLMs are static after training. They do not learn from user data or retain state between sessions. Each inference starts from the same frozen weights. Shaping behavior at runtime requires in-context learning: providing examples within the prompt that demonstrate expected output.

The prompt above uses one-shot learning: a single input/output example that establishes the target format. Without it, the model might return JSON, a markdown table, or CSV with different quoting conventions. The example constrains the output space.

For more complex or variable tasks, few-shot learning (multiple examples) or many-shot learning (dozens of examples) can improve consistency. Here, one example suffices because the format is simple and the task well-defined. More examples would help if input data had greater structural variation or if extraction rules were more nuanced.

The example adds minimal tokens to the prompt but significantly reduces post-processing and error correction.

First-Pass Results and Limitations

LLMs generate output one token at a time, always moving forward. They cannot revise earlier output within a single pass. This autoregressive nature means errors can accumulate, and a misidentified field early in the output can cascade.

On the first pass, the model correctly extracted 44 of 48 records. Common issues included:

- Phone numbers with unusual formatting (periods instead of dashes) occasionally missed

- A hyphenated city name split incorrectly

- One email domain truncated

These are not failures of the approach. This is expected behavior that any production pipeline must account for.

The Second Pass

We can perform a second pass to tighten the results. A simple follow-up prompt handles most first-pass errors:

Review each line carefully referring back to the original data correcting

all errors and omissions.

For more complex extraction tasks, a structured validation prompt works better:

Objective:

Perform a second-pass validation of structured contact data extracted from

unstructured text. Compare the original source data with the first-pass CSV

output to detect and correct:

- Missing information that exists in the source but wasn't extracted

- Formatting inconsistencies (especially in phone numbers and addresses)

- Incorrect parsing (e.g., names combined with emails, ZIP codes in wrong fields)

- Incomplete or misclassified fields (e.g., city/state misidentified as address)

Instructions:

1. Compare entries side by side against the original unstructured text

2. Ensure all phone numbers follow the "(XXX) XXX-XXXX" format

3. Validate emails match correct syntax

4. Realign any data that's in the wrong field

5. Output revised CSV with all corrections

After the second pass, 47 of 48 records were fully correct. The remaining record had an ambiguous address format that genuinely required human judgment.

Validation

To verify results, we can use a different model to check output against source data. Using ChatGPT 4o to compare the final CSV against the original unstructured text:

Issues Noticed:

Address Formatting Issues: “Michael Smith” shows “SF” which should be “San Francisco” to align with standard full city names.

No missing entries detected. The model correctly captured emails, phone numbers, and addresses where available.

Verdict: The output is very accurate, with only one main issue (SF instead of San Francisco). Other than that, the formatting, structure, and missing values handling appear correct.

Even after the second pass, minor issues remain. Human review is still essential for verifying results, especially before importing structured data into other systems.

Why This Works Better Than Regex

Consider this input:

Michael Smith - 415.999.2345

37 Maple Dr, SF, CA 94115

A regex-based system would need explicit patterns for:

- Periods as phone delimiters

- “SF” as an abbreviation for “San Francisco”

- Inferring that “Dr” is “Drive” not “Doctor”

The LLM handles all of this from context. It recognizes that a sequence of digits with periods in a contact block is probably a phone number. It knows SF is San Francisco. It understands that “Dr” following a number is a street suffix.

This contextual understanding is the core advantage. The alternative is maintaining a growing list of edge cases.

When LLMs Aren’t the Right Tool

This approach has limits. It is overkill for highly structured data that already follows consistent patterns. CSV parsing libraries will be faster and more reliable. It struggles with truly ambiguous data where even a human would need additional context.

It also requires verification. LLM outputs should not flow directly into production systems without validation. The second-pass approach catches most errors, but human review remains essential for critical data.

For high-volume production workloads, a hybrid approach often makes sense. Use traditional parsing for common patterns, route edge cases to LLM extraction, and flag low-confidence results for manual review.

Cost and Performance

Processing 48 records took approximately 45 seconds on the A4000 (including both passes). At local inference costs, this is essentially free. The equivalent API calls to a hosted model would cost a few cents, negligible for small batches but meaningful at scale.

More importantly, the data never leaves the local network. For contact information, medical records, financial data, or anything else subject to privacy requirements, local inference eliminates an entire category of compliance concerns.

Summary

Named Entity Recognition represents a category of tasks well-suited to local LLM deployment: structured extraction with clear schemas, tolerance for iterative refinement, and sensitivity to data privacy. Smaller models at reduced precision handle these workloads effectively when paired with appropriate prompt structure and validation methodology.

The key points:

- Smaller models work well for extraction tasks with clear schemas

- Two-pass processing catches most autoregressive errors

- Local deployment eliminates API costs and privacy concerns

- Human review remains necessary for production data